The Art of the Vine: How Grapes and Leaves Shape Anatolian Cuisine

I hadn’t yet grasped how strange the world finds grapes — until we moved to Canada.

Where I grew up, grapes were never just fruit. In fact, I have far more childhood memories of stuffed vine leaves glistening with olive oil on hot summer days, or of swirling tahin pekmez into a comforting winter breakfast, than of eating fresh grapes or raisins plain.

It wasn’t until we moved that I realized: in many places, grapes are viewed as little more than a sweet snack, or a source of wine. But in Anatolia, grapes — and the vine itself — are a living thread that runs through our cuisine, our seasons, and even our sense of home.

Preserved, soured, fermented, wrapped — the gifts of the vine are woven into so many dishes that it’s hard to imagine Anatolian cooking without them. Yet this relationship isn’t unique to us. Across Eurasia, wherever the vine can grow, people have long learned to carry its flavor, its energy, and its meaning through the year — and across generations.

Deep Roots: The Vine in Anatolia

Anatolia — the region we now call modern Türkiye — is one of the oldest grape-growing areas in the world. Archaeological evidence suggests that wild grapevines were domesticated here some 6,000–8,000 years ago.

In ancient times, grapes were not simply a food. They were sustenance — yes — but also medicine, symbol, and spiritual offering. Vine leaves symbolized abundance and renewal. Grape molasses fed generations through long winters. Vinegar preserved both food and wisdom.

And the story of the vine is not static. It is shaped by climate, geography, and human hands — a reminder that “traditional cuisine” is always evolving, adapting to what the land offers and what the season demands.

Kuru Üzüm — Dried Grapes

In Anatolia, kuru üzüm (raisins, or sultanas) are a pantry staple. Drying grapes was an essential way to preserve them before refrigeration existed. A handful of raisins still finds its way into many dishes — from festive rice pilafs to rich lamb stews, and of course, sweet pastries.

Even now, I find that a handful of raisins in a winter dish brings not just flavor, but memory — the warmth of summer carried into the cold months.

Across the region, you see this same instinct: Iranian pilafs, North African tagines, Eastern European desserts. A shared understanding that some flavors are worth keeping close.

Yaş Üzüm — Fresh Grapes

Though fresh grapes are delicious in season, for many Anatolian families they represent a fleeting joy, not the mainstay. We eat them fresh during harvest, but what matters more is what they become: molasses, vinegar, or preserved for winter use.

Grape harvests are still a communal event in many villages — a time of celebration, work, and abundance. This rhythm of harvest, preservation, and transformation mirrors practices from France to Georgia, Greece to Iran — the vine brings communities together.

“Rolling stuffed grape leaves is not a task done alone.”

Pekmez — Grape Molasses

If there is one preserved form of grape I associate most deeply with comfort, it is pekmez.

As a child, a spoonful of tahin pekmez in winter was both food and ritual. Pekmez is thick, dark, and intensely nourishing — a product of patience, reduced grape juice that holds the sun of late summer in its depths.

Before refined sugar was common, pekmez was the Anatolian answer to sweetening. It is still used today not just in sweets, but as a health tonic and an essential ingredient in home kitchens.

Other regions echo this wisdom — with date molasses in the Middle East, pomegranate molasses in the Levant, and maple syrup in North America. Wherever people faced long winters, they found ways to carry energizing sweetness across the seasons.

Sirke — Vinegar

Sirke, or vinegar, is one of the quiet heroes of Anatolian cuisine. Grape vinegar is used in dressings, marinades, and most importantly — pickling.

In the past, vinegar also served a medicinal role: cleansing wounds, warding off illness. In cooking, it balances rich flavors and preserves what must be kept.

The making of vinegar from grape must or wine is a practice shared with countless European and Mediterranean cultures — Italian aceto, French vinaigre, Georgian balsamic-style vinegars. Again, the vine connects us across borders.

“Preserved, soured, fermented, wrapped — the gifts of the vine are woven into so many

dishes that it’s hard to imagine Anatolian cooking without them.”

Şarap — Wine

It surprises some people to learn that Anatolia is one of the world’s oldest wine-producing regions. While wine culture in modern Türkiye carries complex social and religious layers, wine has deep roots here, spanning millennia.

Modern Turkish winemakers are reviving this ancient craft, drawing on both indigenous grape varieties and centuries of skill. And though wine is less central in everyday cuisine, it appears in sauces, marinades, and celebrations.

This adaptability mirrors other vine cultures — from Italy to Georgia — where wine has always been both sacred and practical.

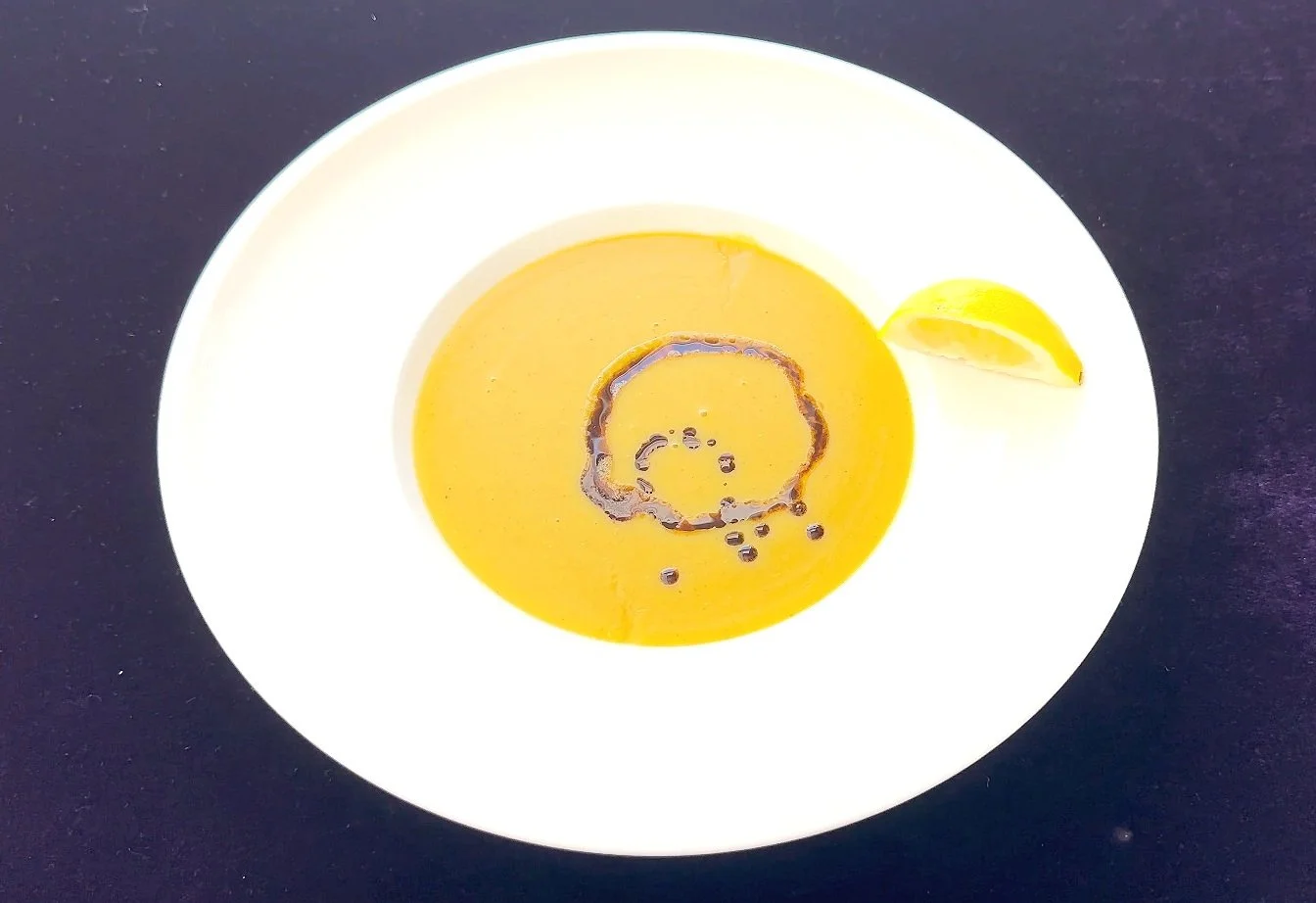

Koruk Ekşisi — The Power of Sour

In Anatolian cuisine, sourness is not an afterthought. It is essential.

Sour grape juice or unripe grape vinegar lends brightness to marinades, balances soups, and sharpens rich stews. This taste for sour echoes across Eurasia — think Persian verjuice, Indian amchoor, Georgian tkemali.

It is another reminder that what is preserved is not just flavor, but balance — a way of making the simplest foods sing.

“Rich in iron and nutrients, pekmez is commonly used during winter months as a

health tonic and an essential ingredient in home kitchens.”

Sarma — Stuffed Grape Leaves

Finally, there is sarma — the dish that perhaps best captures the vine’s role in hospitality, family, and ritual.

Rolling stuffed grape leaves is not a task done alone. In many families, it is an act of gathering — women sitting together, rolling, talking, passing knowledge as surely as they pass the leaves themselves.

Sarma exists in countless forms — Greek dolmades, Persian dolmeh, Levantine variations — but at heart it is about the same thing: turning humble leaves into something nourishing, beautiful, and shared.

A Living Thread

Writing this, I am struck again by how “traditional cuisine” is never static. It is shaped by need, by climate, by migration, by trade, and by the skill and creativity of kitchen fairies across generations! The vine’s journey across Anatolia — and across Eurasia — mirrors this truth.

We preserve what serves us. We adapt what we must. And in doing so, we carry forward not just ingredients, but the wisdom of the land.

In every jar of pekmez, in every bottle of sirke, in every rolled sarma, there is memory — and deliberate progress. A vine that still grows, still teaches, still nourishes us, season after season.