What the Earth Gives: The Human Story Behind Preserved Foods

The older I get, the more I marvel at how much of our cuisine is born not out of abundance, but adaptation.

As a child, I thought the dried peppers strung across balconies and the glass jars tucked away in dark cupboards were mysterious, yet decorative touches. They seemed so normal, so everyday. I didn’t realize I was witnessing an ancient logic at work — one that allowed generations of people to make the most of what the earth gave them, when it gave it.

Looking back now, I see those jars and bundles for what they really are: survival, memory, and wisdom, all packed into a pantry.

And it’s not just in Turkish cuisine. Once you start paying attention, you begin to notice that nearly every traditional food culture — from the Balkans to Korea — evolved with the same urgent question: How do we carry nourishment through time? The answer was never just technique. It was seasonal awareness, trial and error over centuries, and a deep relationship with the land.

In Turkish cuisine — particularly the regional, Anatolian kind still practiced in village kitchens and passed on by heart, not measurement — this relationship is especially vivid in our preserved foods.

Yogurt and Cheese: A Gift of Flora, Fauna, and Patience

It would be impossible to start this list with anything other than yogurt. For Turks, yoğurt is not just a food — it’s a verb (yoğurmak, to thicken or knead), a science, a comfort, a medicine. In Anatolian households, it’s used in everything from soups to sauces, from drinks to desserts.

And cheese? Every region has its own character. Beyaz peynir along the coast, kaşar in the mountains, and lor crumbled over herbs and olive oil in the countryside. These are all reflections of local pastures and climate — the animals graze differently in each place, the milk changes, and the cheeses follow.

You see similar practices in Greek, Persian, Indian, and Central Asian cuisines — where fermentation, straining, and culturing dairy products help them last beyond the short shelf life of fresh milk.

Tarhana: Soup as a Time Capsule

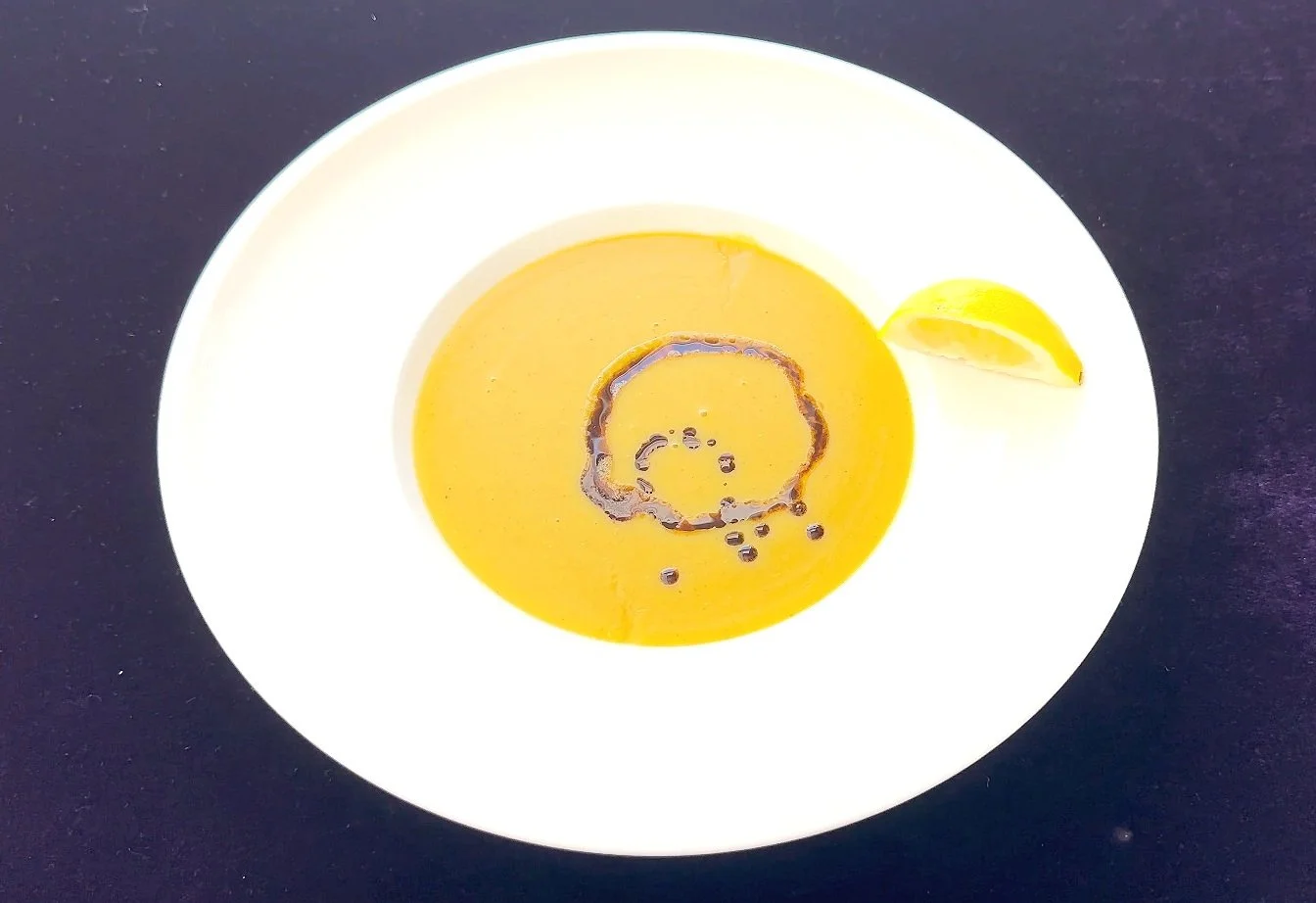

There’s a particular smell in the air when someone’s making tarhana. It’s tangy, almost sour, but warm — like something halfway between yogurt and sunshine. It’s made by mixing yogurt, flour, and seasonal vegetables, then leaving it out to ferment before drying it into flakes or crumbs.

In the middle of winter, a handful of tarhana turns into a soup that fills the house with comfort. It’s a dish that answers the question: “What will we eat when nothing is growing?”

Similar preserved, fermented grains show up across Central Asia and Eastern Europe. The ingredients change, but the logic doesn’t: preserve flavor, preserve nutrition, preserve life.

Bulgur: The Wheat That Waits Patiently

Unlike freshly baked bread or fluffy rice, bulgur is humble, unassuming — but it doesn’t spoil, and it feeds a crowd. Cracked, parboiled, and dried wheat, it’s the backbone of salads like kısır, meatballs like çiğ köfte, and hundreds of other homey dishes.

In the kitchens of Eastern Anatolia, where fresh bread isn’t always accessible, bulgur’s long shelf life makes it indispensable. It’s our version of preparedness. And it echoes in the cracked wheat pilafs of Lebanon, the couscous of North Africa, and the porridges of Eastern Europe.

Salted Red Pepper and Tomato Pastes: Our Red Gold

If you’ve ever opened a jar of homemade biber salçası or domates salçası, you know the smell — sun, salt, smoke, and summer.

These pastes aren’t just ingredients. They’re the concentrated joy of harvest season. They’re what makes a spoonful of lentil soup or green beans taste like home.

In Gaziantep, entire families gather to sun-dry peppers and tomatoes on rooftops before pounding them into paste. It’s a ritual. And across the globe — from Balkan ajvar to North African harissa — the story is much the same: take what’s ripe and radiant, and stretch it across the year.

Pickles: Tart, Crunchy, and Born of Necessity

Pickling is the culinary equivalent of writing a letter to your future self: “Here’s something delicious I saved for you.”

In Turkish cuisine, pickles are everywhere — gherkins, white cabbage, green tomatoes, beets — all steeped in salt, vinegar, and time. They balance out meat-heavy dishes. They bring brightness to oily stews. And like kimchi in Korea or sauerkraut in Germany, they remind us that fermentation isn’t just preservation. It’s transformation.

Molasses: Fruit, Boiled to Its Essence

Pekmez, made from grapes or mulberries, is syrupy, dark, and loaded with iron and minerals. In Anatolia, it’s medicine as much as sweetener. Stir it into tahini for a quick breakfast. Drizzle it over yogurt. Mix it into flour for rustic cakes.

Other cultures have their own fruit syrups — date molasses in the Middle East, maple syrup in North America — but none are quite as dense or as intense as Turkish molasses.

Jams: Sweetness Preserved in Petals and Fruit

When you taste rose jam, it feels like you’re tasting perfume. It’s floral and unexpected — a reminder that flavor doesn’t just come from fruit.

Apricot, cherry, quince, even linden flowers — Turkish jams are delicate, often homemade, and meant to be savored with tea and conversation.

In a way, they are love letters to summer, spooned out in winter.

Stuffed Grape Leaves: Leaves That Tell a Story

Last but never least, vine leaves. Pickled or preserved in brine, they wait patiently in the fridge until it’s time for dolma— rolled with rice, pine nuts, or minced meat.

Making dolma is often a group activity. It takes time, intention, and good company. Every culture around the Eastern Mediterranean has its version — from dolmades in Greece to dolmeh in Iran. But at its core, dolma is a testament to using everything the earth gives — even the leaves.

A Quiet Thread Across Eurasia

These preserved foods aren’t unique to Turkish kitchens — and that’s the beauty of it. Whether it's fermented grains in Central Asia, pickled cabbage in Eastern Europe, or sun-dried pastes in the Mediterranean, these methods span continents, rooted in need, elevated by care.

Yes, modern life has fridges and supermarkets. But in traditional cuisine, we still see the old logic: “Take what grows. Keep what matters. Pass it on.”

We sometimes romanticize tradition — I know I do — but it’s worth acknowledging that traditional cuisine isn’t frozen in time. It’s adaptive, built on countless seasons of trial, error, and wisdom. It knows how to listen to the land. And it quietly teaches us to do the same.

So next time you reach for a jar of pepper paste or unwrap a package of tarhana, remember: you’re not just eating food. You’re part of a long, thoughtful conversation between people and place.

And that, to me, is worth preserving.