Baklava’s Forgotten Beginnings: Ancient Technique Behind the Crispy Layers

Baklava did not begin as the crisp, jewel-like pastry we know today.

But let’s begin with the feeling it evokes now: a tray warm from the oven, the scent of butter rising in soft waves, the gleam of syrup settling into each layered ridge. Before it is ever served, baklava is already a promise—order created from patience and dedication.

Yet this refined dessert has a rugged ancestry.

Long before there was an Ottoman palace, long before Istanbul was a city of empires, there were Turkic and Mongolian pastoralists moving across the wide Siberian and Central Asian steppe. In those early kitchens (portable, practical, and shaped by climate and the rhythms of seasonal migration) cooks would stack sheets of dough with various fillings, pressing and folding them into something hearty enough to travel, yet simple enough to be made on a portable sofra.

The very name baklava points back to these origins.

Linguists trace the word to an old Turkic (later adopted by Mongolian) root, bakl-, meaning “to wrap” or “to pile up.” Balk- was an everyday word for stacking or folding layers. As people moved, traded, and mingled across Central Asia into Persia and Anatolia, the word moved with them through different climates, and thus different flora. Rather than a finished recipe, baklava became an elegant frame by which local flavours, hospitality, and craftsmanship of a culture were represented.

Highly adaptive and versatile in essence, early “proto-baklavas” shifted with each landscape.

Persian kitchens used rosewater and pistachios. Central Asian cooks refined the layering technique. Silk Road trade introduced finer wheat flour and wider access to sweeteners. Nothing stood still. Baklava went everywhere, and every region contributed something different to it. And because of this multicultural adoption, no single place or people could claim it as an origin.

Then came the Ottomans.

In the palace kitchens of Topkapı (the most sophisticated culinary institution of its age) these humble layered pastries were transformed into the fine, modern baklava as we know it today. Famous for their masterful techniques and intense dedication, Ottoman court chefs took the inherited logic of layering and elevated it to an art form. They rolled dough so thin you could read through it. They multiplied the layers for less oil absorption and a lighter experience. They fine-tuned the syrup for a satisfying yet refreshing finish. They pre-cut the baklava for the perfect serving shape, then baked the trays whole, and poured hot syrup over the cooled pastry so it would be absorbed evenly without disturbing a single line cut before baking.

This is where baklava, as we recognize it today, was born: in a kitchen run with military precision (a prominent feature of Turkish society, and thus its institutions) and the imagination of an imperial capital drawing ingredients from across the world. Pistachios from Gaziantep, walnuts from northern Anatolia, honey from Thrace, clarified butter from Rumelia all met in Istanbul…and each had its place in the evolving pastry.

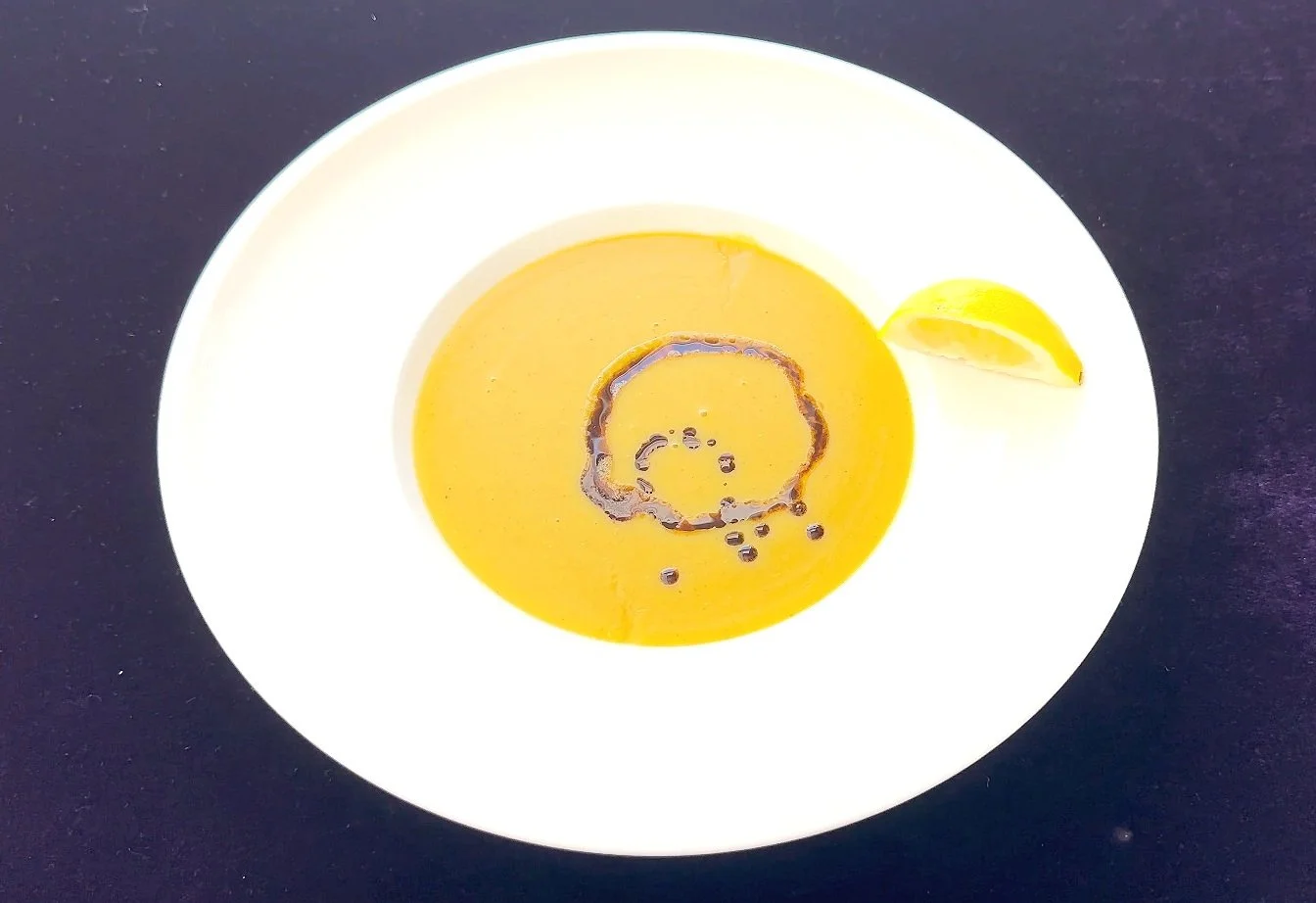

A tray of traditional homemade baklava, fresh out of the oven.

Over time, this fine, elevated baklava made its way into court kitchens, and then into homes as fine flour became more affordable. Many communities within the Ottoman world created their own styles. Armenians, Arabs, Greeks, Albanians, Bosnians, Bulgarians each developed regional variations as the empire’s culinary traditions spread both within and without its expansive borders. But the dessert’s structural identity remained rooted in the techniques perfected in the Sultan’s kitchens.

To eat baklava today is to bite into a long history of elegance and refinement.

It carries the memory of steppe nomads who layered dough and nuts for strength and endurance, the artistry of Persian and Central Asian cooks who added form and fragrance, and the dedication of Ottoman chefs who shaped it into a pastry of extraordinary delicacy.

Claiming that baklava is a single culture’s invention would be an insult to the ageless, timeless, multicultural and multi-regional history of this delicious artifact. Baklava is a layered story, built sheet by sheet, across a thousand years, by a thousand masterful and curious (Fairies’) hands.

This is a dessert that embodied change, versatility, and adaptation, absorbing influences, perfecting itself, and emerging as the golden, intricate confection renowned as one of the most beloved desserts in the world.

A long time ago, back in the first ages of humanity…