In Memory of Atatürk: November 10th, 2025

The morning sun crept through the narrow window, casting a golden ribbon across the blackboard where fresh white chalk gleamed.

The teacher’s hand lingered mid-air, drawing a curve over the word vatan: homeland. Outside, the crisp air smelled faintly of damp soil and smoke from the villagers’ hearths. Inside, the children’s voices hummed in unison as they recited the neat Latin letters that had replaced the curling Ottoman script only a decade earlier.

It was a sound she never tired of…The soft stumbles, the proud corrections, the music of a nation learning to read its own name again.

In 1928 barely 10 percent of Türks could read, but by the end of the decade, that number had already tripled. More than 12,000 new schools had risen from the soil of this newborn republic, many built by the very hands that tilled the land. Her own school stood among them, its plaster still smelling faintly of lime. The (literally) handmade school was the villagers’ gift to Atatürk’s dream that “every child will receive good education such that they can carry themselves and their country into a brighter future.”

The children’s wooden desks were smooth from use, their inkwells chipped at the corners. Yet, to them, these were tools of wit more precious than marble.

A faint knock at the door, hesitant, cut through the rhythm of the lesson. When she turned, she saw the school principal standing there. His shoulders were squared, but his eyes —red-rimmed and glassy— gave him away. He gently motioned her to step outside.

The hallway was quiet. The cool morning sun was draped across the white walls.

“Öğretmen hanım…” His voice broke and lips shut into a thin line as if trying to stop himself. He finally whispered through gleaming eyes. “Atatürk…”

He didn’t need to finish. Her stomach clenched as though the earth itself had tilted. A sharp heat rose from her chest to her face, grief searing everything in its path. For a moment, even the ticking clock on the wall seemed to stop.

She pressed a trembling hand to her chest, her heart tightening painfully, and nodded with eyes wide open, unable to speak.

“How do we tell the children,” the principal plead, his voice tight, tears now streaming.

She straightened her spine, wiped her cheeks and fixed her gaze on the floorboards as she walked back into the classroom. The morning gloom seemed colder. The children looked up, their eyes bright with curiosity. She tried to widen her voice, but words were stuck in her throat. On the board, the chalk letters blurred and swam before her eyes.

“Children…” she began softly, her voice steady. “This morning, the great leader Atatürk has fallen into his eternal sleep.”

The silence that followed felt like a held breath across the nation. Tiny shoulders tensed. One boy covered his face with his sleeve; another pleaded, “But teacher, he promised…”

She knelt between the desks, her knees pressing into the cold floor. “And he did. He kept his promise,” she said through the ache in her throat. “He gave us the tools to stand tall. Look around…This school, these books, these words on the board —they are all his gifts. And now, it’s our turn to protect them.”

As the children’s tears mingled with hers, she thought of her mother who had never learned to read, who had lived her life in service to her family, unable to make her own way in the world. Now her daughter stood before thirty children, teaching them the alphabet of a new age.

Outside, the wind picked up, carrying the scent of damp earth and burning wood. Her eye caught the low crimson flag in the schoolyard. Somewhere in the distance, a train whistle echoed long, low, and mournful —as if the whole land was letting out a sigh of grief together.

At that moment, she realized: Atatürk really was gone, but he would not be forgotten. His voice lived in the turn of a softened page, in the sound of chalk against slate, in the light of a child’s eyes when they read their first word. Her tears fell silent onto the lesson plan she’d written that morning, “The New Republic: A Gift for the Future.”

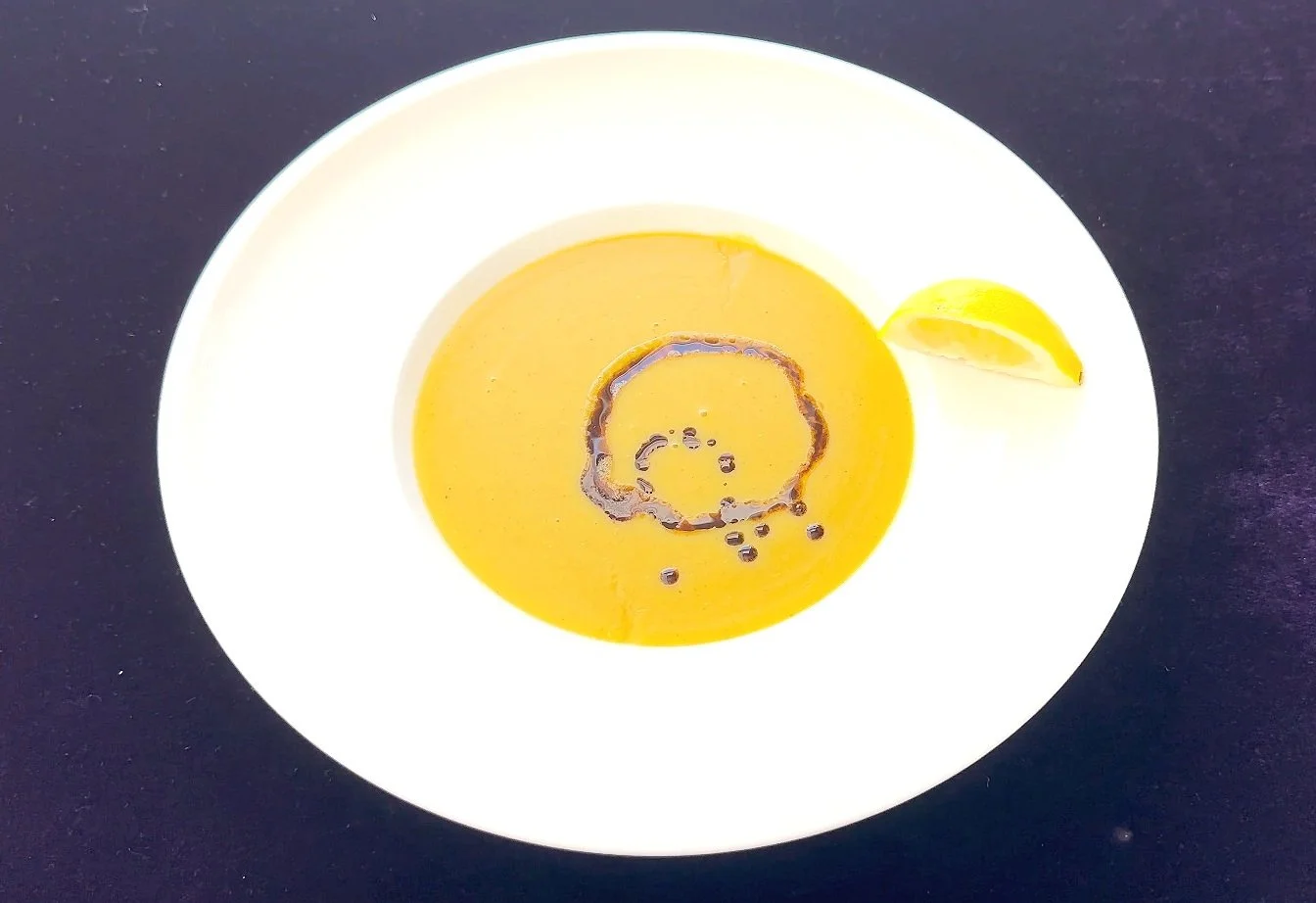

And in her heart, though it ached like an old wound, there was also something bittersweet that warmed you from within.

—Thursday, November 10th, 1938

P.S.:

Between 1923-1938, more than 12,000 schools were built in the new Republic of Türkiye (founded in 1923); the number of teachers rose from 4,000 to 16,000.

The 1924 Education Law guaranteed co-education (prohibited under the late Ottoman rule) and by the mid-1930s, women made up nearly 25% of all teachers in primary schools.

Over 1.5 million Turkish citizens attended “Nation Schools” (Millet Mektepleri) to learn the new Latin alphabet after 1928. (The Latin alphabet was easier to learn and better suited for the variety of sounds and the highly adaptive nature of the Turkish language, compared to Ottoman script, which used a mix of Persian and Arabic letters to represent Turkish sounds.)

In 1927, only ~10% of Türkiye’s population was literate; by 1935, this number had risen to ~20%, with nearly half of new literates being women —a revolutionary shift at the time, especially for a new country with war-torn people of diverse backgrounds. But they had fought for and united under one name that embraces everyone who honour it: Türk.