6 Universal Methods of Preservation

For most of human history, it was less about ‘what to cook tonight’, and more about ‘how do we make the bounty of this season last until the next’. Preserving food wasn’t a hobby. It was survival, celebration, and creativity all at once.

In Anatolia, where seven climates and four distinct seasons have shaped life for millennia, food preservation became both art and necessity. From fertile plains heavy with wheat to coastal waters rich in fish, each harvest demanded foresight: what will carry us through winter? Which flavours will we want when the snow buries the garden?

The answers echo across cultures worldwide. In fact, almost every society on earth converged on the same six preservation methods. And though techniques differ, the logic is universal—limit spoilage, extend nourishment, waste nothing.

Let’s explore these six universal methods, and how they’ve been practiced in Anatolia for thousands of years.

1. Drying & Salting

Purpose: To strip away moisture and stop microbes before they can spoil the food.

Across the world, this is humanity’s oldest preservation trick. Nordic fish strung on wooden racks became stockfish. Strips of meat dried in Asian steppes became jerky. In the Andes, potatoes were freeze-dried into chuño to last the year.

In Anatolia, the Turks perfected pastırma—beef pressed under layers of salt, fenugreek paste, and spices, then dried in the open air. Sucuk, spiced sausage, was another favourite of nomadic horsemen, hung to dry as they moved across the steppe. Dried figs, apricots, and grapes were strung on thread and tucked away for winter.

Drying and salting turned abundance into insurance, and flavour into memory.

2. Smoking

Purpose: To protect food with fire and smoke while adding depth of flavour.

Indigenous peoples of North America smoked salmon for the long winters. Central Europeans smoked pork into hams that perfumed whole villages.

In Anatolia, smoking was gentler—often just enough to add a crust and slow spoilage. Fish caught in the Black Sea, or game brought in from the hunt, might be lightly smoked before being salted or dried.

Smoking often wasn’t used alone. It was another layer—part of a toolkit, never a standalone.

3. Fermentation & Pickling

Purpose: To transform food with microbes and salt, turning fragility into resilience.

Few techniques are as universal—or as miraculous—as fermentation. Korean kimchi, Eastern European sauerkraut, Mexican encurtido, Chinese tsukemono—all share the same principle: submerge vegetables in brine, let time and microbes do the work.

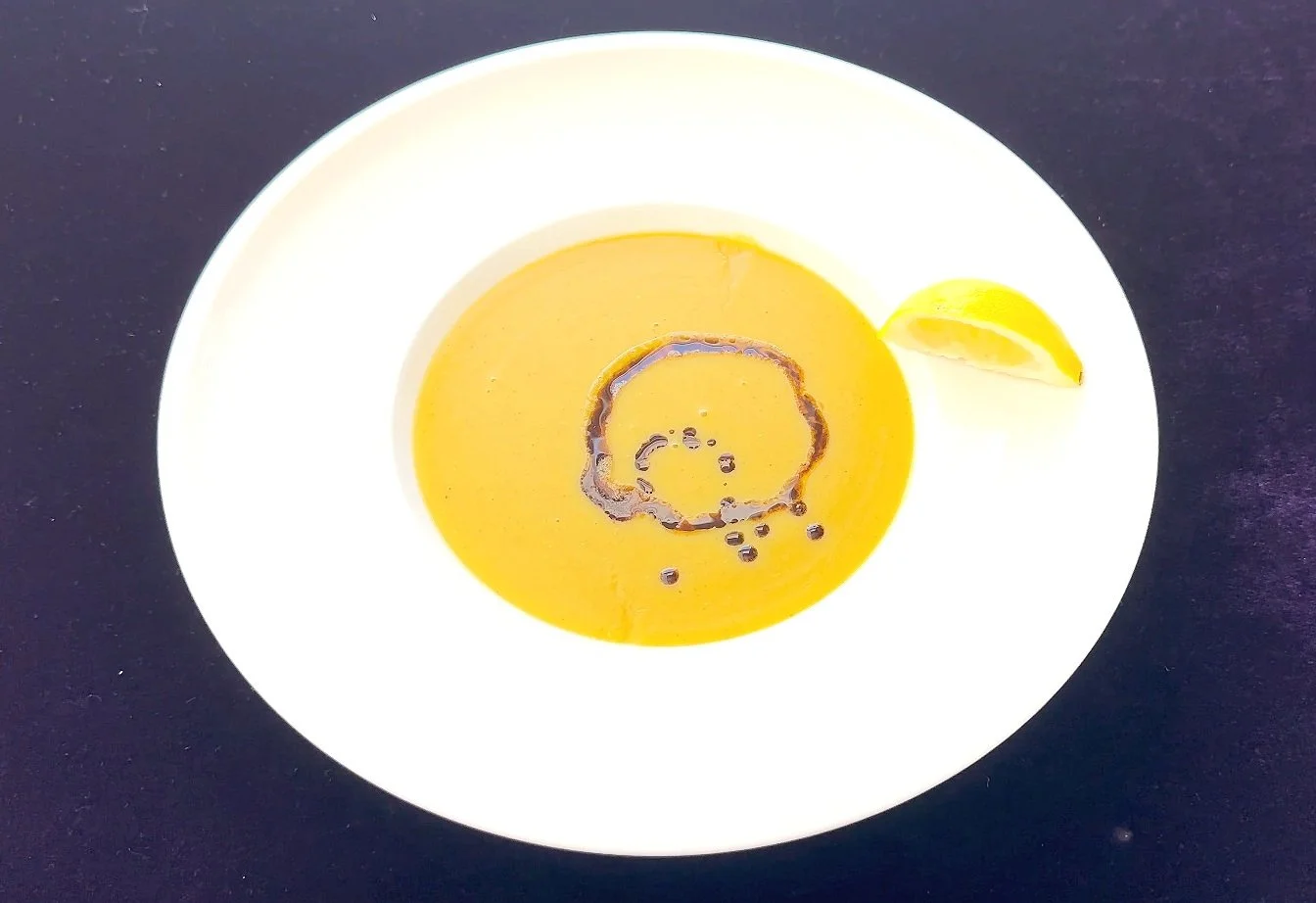

In Anatolia, turşu (brined pickles) remains a winter staple. Cabbage, peppers, cucumbers, even grape leaves were salted and stored in clay jars. Tarhana—a fermented mix of yogurt, wheat, and herbs—was dried into hard nuggets, ready to become soup on cold nights. And of course, yogurt itself is a form of dairy fermentation, embraced daily across Turkic and Anatolian life.

Fermentation was never only about survival. It created flavours—sour, tangy, complex—that became signatures of cuisines.

4. Sugaring & Concentrating

Purpose: To harness sugar as both preservative and pleasure.

In India, fruits were candied. In Europe, marmalades and conserves filled pantries. In Central Asia, fruit leathers rolled like scrolls of summer.

Anatolia contributed pekmez (grape molasses), simmered down until thick and dark, and pestil (sun-dried fruit leather). Apricots, mulberries, and plums became chewy strips of concentrated sunshine. Jams (reçel) were often cooked in copper pans until jewel-bright.

Sugaring preserved more than food—it preserved joy. When fresh fruit was long gone, one spoon of jam or sip of molasses kept the memory of orchards alive.

5. Cooking in Fat (Confit/Kavurma)

Purpose: To seal meat away from air, keeping it tender and safe.

The French call it confit. In England, there was jugging. In Anatolia, it was kavurma: cubes of lamb or beef slowly cooked in their own fat, then submerged under a cap of rendered fat for months of safe keeping. Soldiers carried it, families prepared it before harsh winters, and later, cooks used it to flavour pilafs and stews.

Fat preserved the meat, but it also gave it back—spoonfuls of kavurma became the base of hearty meals, proving preservation was never separate from cooking.

6. Parboiling (Grains like Bulgur)

Purpose: To pre-cook and dehydrate grains, making them lighter, longer-lasting, and easier to prepare.

Parboiling deserves a spotlight. In Anatolia, whole wheat was boiled, sun-dried, then cracked into bulgur—a grain so durable it could last months, so quick it could cook in minutes. It was one of humanity’s first “convenience foods”.

Elsewhere, parboiling rice in South Asia and Africa made it more stable and nutritious. But bulgur stands out: a uniquely Anatolian answer to feeding households quickly, nutritiously, and with minimal waste.

From soups and salads to pilafs and köfte, bulgur shows how preservation can become the very heart of a cuisine.

Preserving in Layers

Rarely were these methods used in isolation.

Meat salted, dried, then smoked.

Grapes boiled into molasses, then sun-dried into fruit leather.

Vegetables salted, pickled, then buried in clay jars underground.

This layering maximized shelf life, nutrition, and flavour. It was not just survival—it was strategy, creativity, and care.

What About Cooling and Cellars?

Every culture has relied on cool storage—root cellars, caves, pantries. Today, we rely on refrigerators. But because these methods are so universal, they form the background to all the others, not the centerpiece.

Modern Times

Today, most people think of jarring, canning, or freezing when they hear “preservation.” These are invaluable, but they’ve led us to forget the basics. Many of us feel nervous about fermenting a jar of cucumbers, even though our grandparents wouldn’t have thought twice.

In a future blog, we’ll explore these modern techniques and how they connect to the older traditions.

How to Begin (Actionable Advice)

Preservation doesn’t need to be daunting. Start small:

Drying: Hang a bunch of fresh herbs upside down in the shade.

Pickling: Try our recipe for sour cucumber pickles (cornichon).

Sugaring: Make real fruit leather at home with nothing but fruit and patience.

Bulgur: Stock your pantry with bulgur (a shelf-stable grain that cooks in minutes).

Ask: Talk to older relatives! How did they keep food through winter? How did they use it in daily recipes?

Even one small step connects you to the same wisdom that has carried families through centuries.

Conclusion

Food preservation is a universal language. From the fjords of Norway to the plains of Anatolia, humans found the same six answers to the same eternal problem: how to make abundance last.

Anatolia, with its crossroads of climates and cultures, turned preservation into an art form. Not just to survive winter, but to waste nothing, to flavour everything, to carry memory forward.

When you dry a handful of herbs or tuck away a jar of pickles, you’re not just saving food. You’re joining a story thousands of years old—a story of resilience, care, and the deep human desire to keep life’s flavours alive.